History of alchemy (II): the Byzantine world and the Islamic world

After a review of alchemy in Egypt, Greece and Rome, the so-called Dark Age, the Middle Ages, arrives in Europe. However, although a lot of knowledge is lost on the continent, also the copying work and, above all, the contact with Islamic culture, also widespread as Arabic, will give way to a new era with an alchemy that, although it shares some features with the already views, also presents new features.

-Byzantine world

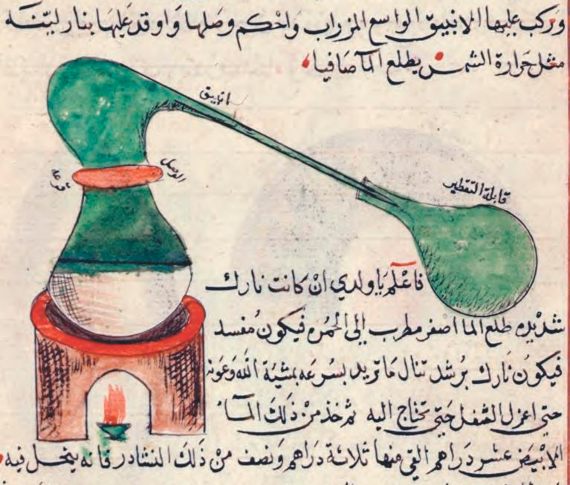

Byzantium, halfway between the East and Europe, tried to preserve the writings of the ancient Greek alchemists, while also being carried away by the mysticism of the Church of the East. The writings of Zosimus will be basic, but we will also find new characters who will be given great importance, such as Mary the Jew - also called Mary of Alexandria -, mentioned precisely in Zosimus' texts, and to whom the invention of two works is attributed. alchemical tools, the tribikos (three-arm still used for distillation) and the kerotakis (vacuum reflux vessel), as well as the heating of materials through a liquid, which even today is known as a Bain Marie . But along with her we find many other texts of historical or mythical figures in which attribution and fantasy are mixed, such as those attributed to Cleopatra the alchemist (confused with the queen of Egypt), Hermes, Agathodaimon ("the good demon") , Isis...

The most important manuscripts of Byzantium, however, are those of Zosimus. Perhaps because his alchemical vision fit perfectly with the Christian religion: in the so-called Visions of Zosimus, in the work Γνήσια ὑπομνήματα (Genuine Memories or Authentic Memories), the alchemical operations follow a ritual pattern of destruction-torture, death and resurrection , easily identified with the double divine nature. This is reaffirmed in the pseudo-alchemical literature (he did not intend it that way) of Filipo Monotropos (10th century), where the double or changing nature of Jesus Christ justifies that this possibility exists in a nature created from his own essence.

However, with the exception of the emperors Julian the Apostate and Heraclius, alchemy did not receive any concrete support. Hence what we are going to find are mainly comments on the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists, and the new Persian alchemists, but not many original works. It is not necessarily something negative, since thanks to the Byzantine copyists a first corpus of alchemy from antiquity was obtained. Among the alchemical works we will find rather pragmatic purposes, such as Miguel Psellos (11th century), in his How to Make Gold - although it seems like a simple academic treatise, not intended for real practice.

Olympiodorus and Stephen of Alexandria (VI century) have separate works in which, among their thoughts on Platonic philosophy, they include aspects of nature or astrology, and also alchemy. From Stephen or Stéfanos of Alexandria we have alchemical works, such as the Apotelesmatike Pragmateia, because he analyzes, as a good doctor and naturalist, the changes of matter, such as putrefaction and its capacity to give life, as in the case of fertilizer. for the plants. It is said that Stephen of Alexandria revealed one of his alchemical secrets to a Christian refugee soldier named Callinicus: the so-called Greek Fire, an incendiary weapon that saved Constantinople on multiple occasions from Muslim attacks. It was, it seems, a liquid chemical compound, which burned even in contact with water, which gave an unbeatable defense to the Eastern Christians, especially when used with siphons, as if they were pressure hoses. Unfortunately, its composition was secret to avoid its use by enemies, so much so that the recipe has never been found in writing to be able to recreate it.

This is a clear example of how alchemy in Byzantium sought a useful application. For this reason many treatises on goldsmithing and metal work were considered within the works of alchemy, and also why it cannot truly be said that it prospered. Partly it may have had to do with Christianity, admiration for the ancients, and partly because the political and economic environment could not allow it. However, despite pragmatism, Byzantine alchemy was always closely linked to religious mysticism and the esoteric world, such as astrology or gematria.

-Islamic world

Be that as it may, from the 7th century onwards, alchemy seems to continue exclusively in the Muslim world. The name of Arab alchemy is the product of a bad generalization, since we will find many different ethnicities among the different scholars (Persians, North Africans...) There are those who believe that in this period, through contacts through commercial and cultural routes with the Indian subcontinent, alchemical ideas reached China. However, in subsequent articles it will be seen that the alchemy developed in China seems indigenous, and it may, perhaps, be the Arabs who knew Chinese alchemy and distorted it, since there are no Arabic translations of Chinese works. Regardless of this aspect, alchemy is known through Egypt and the Middle East, as well as through Greek translations, around the 7th century, although it was not until the 10th century that it spread. In the work Al-Fihrist, or Book of the Catalog, by the biographer Ibn al-Nadim, it is said that Khalid Ibn Yazid was the first Muslim who became interested in alchemy and requested the first translations, and another key figure, Jabir, is also mentioned. (Jabir ibn Hayyan), a Persian chemist whose very existence is disputed, but whose works, copied many times, were written between the 7th and 10th centuries.

Jabir is also known through European translations as Geber. He is credited with the experimental, purely chemical study of distillation (this type of work would give rise to great methods for the creation of perfumes, oils and soaps), as well as, following the Aristotelian division of the four natures of matter: humid, dry, cold and hot, to interpret that the four elements came directly from the fusions of these aspects, so that, knowing their percentages, it was also possible to separate them, identifying "the substance", the unifying element that causes the unique formation of the matter. His is the division of mercury as water and earth, and sulfur as fire and air, and in some works he seems to express that these elements are the basis of the vegetal and mineral world. This thought of what matter really is made him go from the Greek exclusivity of metals to the introduction of vegetable and animal matter as well, taking the first steps of organic chemistry. On the other hand, Jabir divided minerals into three groups: volatile, meltable metals and non-malleable substances, and assigned certain numerals to each one, which fulfilled a mathematical as well as categorical value within "creation."

The Jabirian corpus is one of the most extensive, and of course includes many works of dubious authorship. Among the alchemical texts, Arabic magic squares also appear to achieve the balance of the elements. There are also multiple pseudoepigraphs of Ja'far al-Sadiq, who is said to have been Jabir's teacher. His works include a poem, alchemical works, and various treatises on geomancy and amulets, as well as numerological and encryption issues.

Arab science established its values on verification and results, which was strange in its application to alchemical science, since in some cases, the different chemical reactions actually caused a new matter (such as the case of caustic soda). or tinctures), but when it came to working with metals, alchemy was far from obtaining gold from any metal, despite the basis that indicated that all metals were the same, with different amounts of substances that gave rise to one and the other. Let us not forget that gold is also a symbol: the most perfect of metals, the obtaining of which must join the path of a perfection that is also human and spiritual. For this reason, alchemy in the Arab world was included among the theoretical and propaedeutic sciences, that is, with the purpose of helping human well-being. This made it the focus of criticism from many philosophers, who considered that alchemy sought unrealizable and unnatural things, leading to fraud and deception. Avicenna himself (ar. Ibn Sina, 980-1037) said that he had studied alchemy and did not find logic in any argument, despite the fact that, on the part of critics, he found equally futile arguments. We will find many writings with mythical figures in the background, as was the case in Byzantium: Hermes or Agathadhimun, like his disciple (who is none other than the Byzantine Agathodaimon), to whom the Risalat al-hadhar, Epistle of warning, discovered in India, is attributed.

Little by little, Arab alchemy is also developing a mystical and religious facet, as had happened in Byzantium, in relation to the "substance", also called "elixir", considering that the First Substance can be reached, the natural base of which all other materials would arise, and consequently, their control. God is One, and everything returns to Him, so that human beings should be able to at least glimpse that primal and unique matter of Creation. Thus, alchemy began to have its most practical facet and its most "intangible" facet, since the research work also encouraged philosophical and religious reflection, and gradually, the alchemical art was called "Wisdom." Nicolas Flamel will be the first to state, from his particular vision of alchemy, that the Alchemical Work makes man better, since it brings him closer to the Primordial. Islamic alchemy will also include hermetic and gnostic alchemical traditions. It will also be related to astrology, since the cosmic order and melotesia will be a mirror of the works of manipulation of matter and spirit, and whose works will be of great interest in the Western world. Perhaps the most relevant case is the astrological works of Alfonso X, who directly defined alchemy as: "astrology applied to life and the transformation of metals." Likewise, the first mentions of colors and planetary symbolism in alchemy are attributed to the Muslim world, probably due to the mixture of astrology and astronomy in their works.

Starting in the 12th century, alchemy was reintroduced little by little but with great success in European society thanks to the work of compiling Greek works by Greek thinkers, such as Theophrastro, and the Arab alchemical works themselves. Many words of states, substances and alchemical tools will take the Arabic name, which attests to their importance. We can cite, for example, al-tannūr, in Latin athanor, which is the name given to the oven; al-uthāl, translated as aludel, the vessel of sublimation; and so on with alembic, alcohol, elixir...

Little by little, Arab alchemy is also developing a mystical and religious facet, as had happened in Byzantium, in relation to the "substance", also called "elixir", considering that the First Substance can be reached, the natural base of which all other materials would arise, and consequently, their control. God is One, and everything returns to Him, so that human beings should be able to at least glimpse that primal and unique matter of Creation. Thus, alchemy began to have its most practical facet and its most "intangible" facet, since the research work also encouraged philosophical and religious reflection, and gradually, the alchemical art was called "Wisdom." Nicolas Flamel will be the first to state, from his particular vision of alchemy, that the Alchemical Work makes man better, since it brings him closer to the Primordial. Islamic alchemy will also include hermetic and gnostic alchemical traditions. It will also be related to astrology, since the cosmic order and melotesia will be a mirror of the works of manipulation of matter and spirit, and whose works will be of great interest in the Western world. Perhaps the most relevant case is the astrological works of Alfonso X, who directly defined alchemy as: "astrology applied to life and the transformation of metals." Likewise, the first mentions of colors and planetary symbolism in alchemy are attributed to the Muslim world, probably due to the mixture of astrology and astronomy in their works.

Starting in the 12th century, alchemy was reintroduced little by little but with great success in European society thanks to the work of compiling Greek works by Greek thinkers, such as Theophrastro, and the Arab alchemical works themselves. Many words of states, substances and alchemical tools will take the Arabic name, which attests to their importance. We can cite, for example, al-tannūr, in Latin athanor, which is the name given to the oven; al-uthāl, translated as aludel, the vessel of sublimation; and so on with alembic, alcohol, elixir...

The first translation into Latin was made in the School of Translators of Toledo, the Liber de compositione alchemiae (1144), by Robert of Chester, taking much of Risālat Maryānus al-rāhib al-ḥakīm li-l-amīr Khālid ibn Yazīd, (The epistle of the wise monk Maryanos to prince Khālid ibn Yazīd), both being semi-legendary characters, and the text having parts that do not really belong to said epistle. Other works that spread throughout Europe were the aforementioned Books of Jabir, translated by Gerard of Cremona, and mystical and alchemical texts attributed to different authors, such as the De anima, falsely attributed to Avicenna, the Secreta secretorum or Siir al-Asrar, attributed to the doctor Abū Bakr ibn Zakariyā' al-Rāzī, or the famous Emerald Tablet, the first mentions and texts of which appear for the first time in the treatise Sirr al-khalīqa wa-ṣanʿat al-ṭabīʿa or Secret of Creation and art of nature, also known as the Book of Causes (Kitāb al-ʿilal).

Pietro V. Carracedo Ahumada - pietrocarracedo@gmail.com

Bibliography:

-Eberly, J. Al-Kimia: the Mystical Islamic Essence of the Sacred Art of Alchemy, Sophia Perennis, 2004

-Hill, D. R. Islamic Science and Engineering, Edinburgh University Press 2019

-Magdalino, P. The Occult Sciences in Byzantium, La Pomme d'or, 2006

-Morelon, R. Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Technology, alchemy and life sciences. CRC Press, 1996

Related Posts:

>History of alchemy (I): Egypt, Greece and Rome

>History of occultism (II): The Middle Ages

>Ilm-al-Raml or Science of Sands: Western Geomancy

>The lapidary of Alfonso X the Wise: minerals and astrology in the Hispanic Middle Ages