Review: Exhibition Plants and Witchcraft at the Complutense University of Madrid

A few days after the end of the exhibition, it was possible to us to visit it, and here is a review-summary so that you can also evaluate the exhibition, from anywhere, and promote more activities like this one. Accommodated in a not very extensive space, the exhibition is quite complete, accurate, and to a certain extent welcoming. With brooms on the ceiling, a full moon projected on the front wall, hanging bats and the adapted recreation of the fireplace with the boiling cauldron in a possible witch's cabin, the setting of the whole does not leave anyone indifferent, although a more space for such a complex issue. Leaving aside the scenographic recreation, several showcases are arranged, some low and others high, to observe the selected plants and other items.

Among the showcases or on them we find the information panels with general information but also curiosities. Perhaps this is the most interesting part of the exhibition, since for the layman in herbology and biology, the sample of specimens does not allow him to deduce much more either. However, the labels provided a lot of extra information. The inclusion of curiosities, on the other hand, turn the tour into the beginning of possible paths to personal research and interest that, if they had been exposed in a lengthy quote of authors or exhaustive texts, would not have achieved the sensation of a swift visit that the place offers.

If we are guided by the apparent order of the exhibition, we begin with a panel where the subject is presented: Plants and witchcraft. A successful introduction to start the tour bearing in mind that we are not in a purely plant exhibition. It refers, among the issues related to the evolution of the duality of the use of plants, from the figure of the shaman, the apothecary, the doctor, and between the religious and the scientific vision, the magic, the character of the witch, an expert in herbs whose functions are not always verifiable. From here it goes to healing herbs and the medieval vision of negative and manipulative witchcraft, associated with the services of the devil, an image that, on the other hand, is the one that has lasted to this day. As one of those curiosities that the exhibition included the mention of nitrophilous plants, which require nitrogen and organic matter, which can be easily found in cemeteries and other abandoned places that, coincidentally, witches visited to prepare their concoctions. In addition, the fact of collecting them at sunset was not due so much to a matter of hiding bad actions as to the fact that the alkaloids, responsible for the psychoactive reactions of their intake, increased after a whole day receiving sunlight.

Some of the most widely used and scientifically recognized plants for their effects, which had uses of a shamanic, mystical, witchcraft nature, are indicated at a geographical level. From Africa they exhibit iboga, which, grated, powdered or infused, stimulates the central nervous system, producing hallucinations. From South America peyote, San Pedro, are mentioned, which in addition to religious uses in Mexico and the Andes, are also used in psychiatry. Ayahuasca, caapi or yajé also appear, as well as the teonanácalt mushroom or meat of God. In Asia we find Indian hemp, cannabis, or the Amanita mushroom, whose ceremonial use in areas as disparate as India, Siberia and Mesoamerica highlights the supposed cultural heritage of Asians in their still little-known trips to the American continent. From Europe we have the case of mistletoe and oaks among the Druids of the Celtic world, as well as the so-called ergot, a hallucinogenic fungus whose synthetic derivative forms LSD. Its use already occurred in the Greek kikeon, ritual drink of the Eleusinian mysteries; and its use increased during the Middle Ages, perhaps because of witchcraft, perhaps because of its medicinal values.

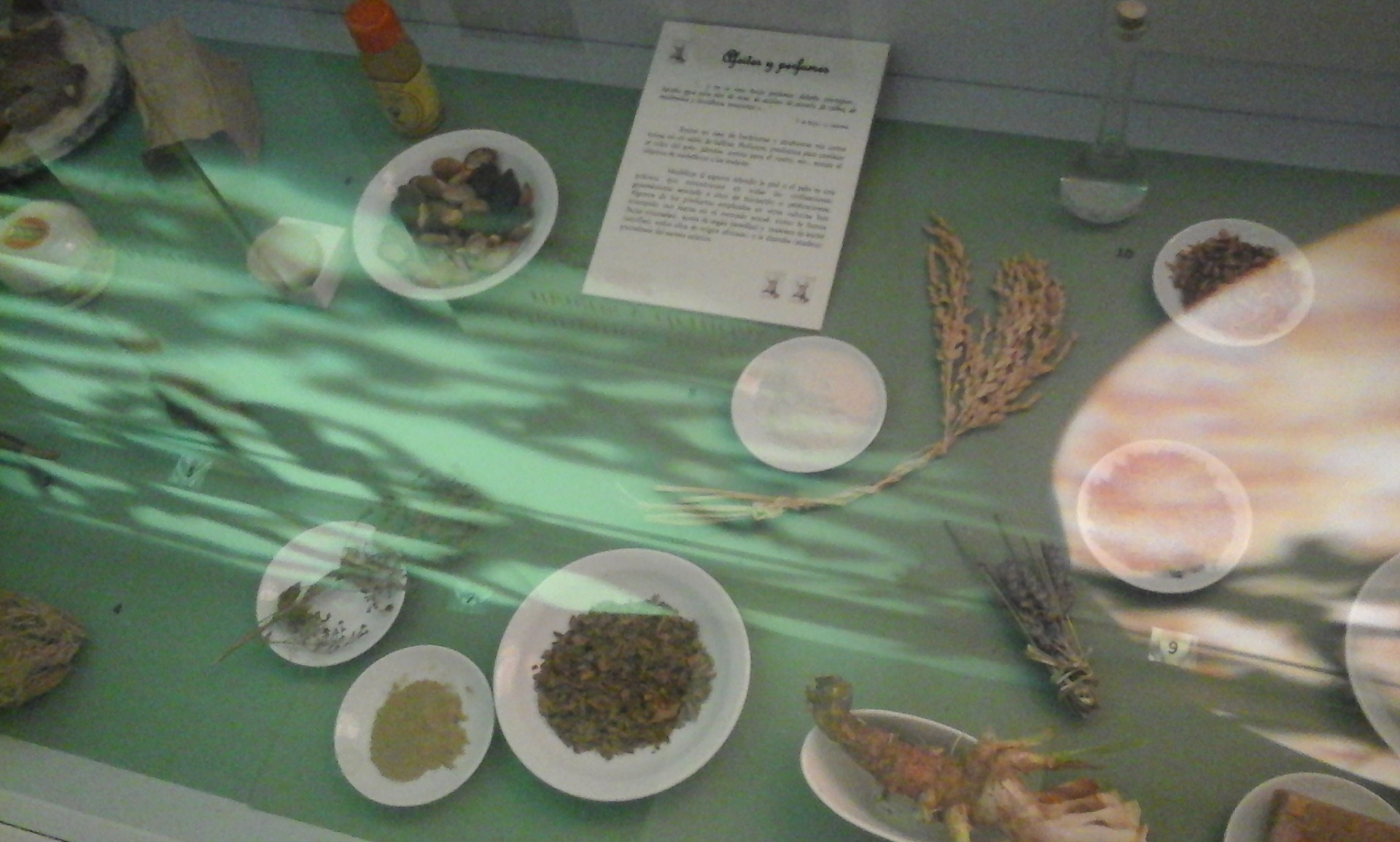

The use of plants in oils and perfumes is linked to medicinal use, but also to aesthetic and purely magical use, along with incense and burning sticks. This is the case of the resins burned to purify places or people to induce a special atmosphere for divination or spell development.

As for the elixirs, together with the purely poisonous ones we find those with a love function, normally prepared with species of the aphrodisiac, spirituous type, and some others with tryptamines, present in the sensations of falling in love. Of course, like everything else, the control that should be had in the production and ingestion of them was more than necessary to avoid overdose with disastrous results. These results included hallucinations, skin redness, photophobia, disorientation, paralysis and death itself. A related curiosity that the exhibition shows us is the probability that in Salem, the accusation of witchcraft and poisoning came perhaps from bad fermented rye bread where a fungus called Calviceps purpurea would proliferate that produces LSD acids, with the consequent hallucinations. However, there were also antidotes such as muscarine, known for its virtues against poisoning.

Four plants enjoy supremacy in magical/medicinal use. Henbane, stramonium (jimson weed), belladonna and mandrake. Each of them has many peculiarities, henbane was used as poison by the Gauls, which impregnated the tips of their arrows, as well as during the Middle Ages, following the magical idea that like influences like, they were used for pain of teeth and other dental issues. We know about stramonium that in the Greco-Roman world it was used as an aphrodisiac, especially in Bacchanals and Dionysian festivals, but Dioscorides himself already warned of its possible toxicity. However, its seeds are known for their effectiveness against asthma. Many legends existed around belladonna, known as the coven plant, such as the one that only its spirit and powers arose on the night of the dead, Halloween or Walpurgis, as well as in Egypt and Syria it was used to improve mood. Also, its Latin name Atropa belladona, refers to atropos, the Moira that cut the thread of life, referring to its high toxicity. And par excellence, the mandrake is perhaps the best known of the four, not only for its famous screeches when plucked, but also for the numerous rituals that take place around it: from marriage rites to the creation of anesthetics, passing through its literary visions where it is used by Circe to turn Odysseus' companions into pigs. All this motivated by its anthropomorphic appearance, since its roots well form a figure that can resemble a body with legs and arms.

The showcase with vegetables and hard shelled fruits deserves special mention, as part of the plants and their use, especially as containers of liquids or incense and lights, to be used as lanterns, also in particular rites, such as this is the case of turnips or pumpkins on the night of the dead. It is curious the inclusion of maracas and other instruments arising from the manipulation of these fruits, as part of the magical-religious issue, of the importance of music in the ritual.

Incredible coincidence and rarely taken into account is the fact that brooms obviously have a plant component, of which there are more than 170 varieties of plants chosen for the specific purpose of use as brooms, such as sorghum and millet, the palm, the balls... some even take the name, such as the broom, the "plumerillo" (little feather duster) or the broom-broom. Although the idea that witches fly is indisputable in most cultures, their association with brooms, coming from the Middle Ages (appearing for the first time in a Canon Episcopi of the 10th century), may be due both to their identification with feminine tasks, as to more obscene visions of its use.

Herbs have also functioned as a defense against witches, despite the fact that they are the main manufacturers of ointments and filters with them. This is the case of the golden thistles, the fennel flower or the sempervivum (always alive, in latin) that symbolize the sun, or the broom branches, examples used throughout rural Europe, as well as scarecrows, figures on the roofs and chimneys, arranged there in the belief that they flew over the houses, although the main defenses were always in doors and windows, where garlic gains its fame by a landslide to drive away evil spirits. Hipericum or St. John's Wort was known as Fuga daemonium, because its burning drove away evil spirits and its ingestion freed those possessed and revealed the unspeakable secrets of those accused of witchcraft.

On the other hand, they also warned of the presence of witches, as when one comes across the so-called "witches' brooms", bushes infected by fungi that intertwine the branches and blacken them until they form balls in the middle of the grove.

Finally, we come to the part of present-day survival. They are not only found celebrating seasonal festivals where rituals of a magical nature, such as the gathering of certain herbs, the lighting of bonfires, the burning of incense or the emptying of vegetable lanterns, but also in literature. We pass from the Greco-Roman visions of magic in epic poetry (Circe, Medea, Ericto...) or the novels of Apuleius, to the witch with cauldron, cat and broom. This image appears for the first time in an engraving by Brueghel the Elder from 1565, although there are earlier representations attributed to El Bosco (1450-1516), where what would be "models" of this witch image already appear. The evolution of the magic images has taken two paths towards the malefic and beneficial character, but in the case of the witch, perhaps because of her sex, perhaps because of linguistics, the predominant image continues to be, at least, disturbing, and initiatives like this allow us to enjoy her entire world without so much prejudice.

Pietro Viktor Carracedo Ahumada - pietrocarracedo@gmail.com